A quick Google search for people’s preference of odd or even numbers will have our AI overlord telling us that people’s inclination is split, or slightly partial towards even numbers.

Some cases for even numbers:

Even numbers appear more frequently in basic mathematical contexts (like multiplication tables), making them more familiar and readily processed.

Even numbers are often linked with concepts like balance, stability, and order, while odd numbers are sometimes associated with creativity, individuality, or even "oddness".

In marketing, odd numbers (like $19.99) are often used to create the perception of a deal or discount, while even numbers (like $20) are used for luxury items.

Some cases for odd numbers:

In group settings, an odd number of people can prevent ties when voting or making decisions based on majority rules.

In design, art, and even food presentation, odd numbers of elements are often seen as more visually interesting and harmonious, creating a sense of balance and intrigue.

The differences are there, but how do they materialize?

If you have talked to a routesetter about routesetting at length (sorry for your losses), there is one question that always comes up. Is it art or design? There are stalwarts in each camp with their reasoning for both. If we are creating a product where the goal is for people to interact with it in a seamless way, it has to be design. If we are creating a visual experience for people to find their own experience with, it has to be art.

The question that we always get about routesetting is “why are you always putting 3 holds in a line?”

Design Fundamentals

Disclaimer: I have no education in design. I spent most of my life thinking I didn’t have a creative bone in my body. I sucked at drawing, music, photography and whatever else you try in your late teens and early twenties. Unknowingly, routesetting became my creative outlet.

I had not done research into the design elements and principles until around 2 years ago, when two of my peers, Connor Perzely and Chris Feghali, brought them up to me. Connor designs products at a steel mill and Chris is a painter. They had both mentioned that I was applying these principals in my routesetting. In my mind I was doing what I thought looked appealing, but there was a deeper dialogue.

On the heels of last week’s article on the “LIC Style,” one of the practices that has been imprinted on the setting is putting 3 holds in a line. This usually pops up in at least one place on every route in the gym. But this didn’t start with me.

When I started at LIC in 2017, I had the privilege of working with Big Chris for a short period of time before he moved on to open his own gym. In my time working at LIC, I’ve never heard people more upset about a routesetter leaving. People loved his routes, and it’s because he focused on one thing: intuitive design. BC’s routes had more holds on them than most, with horizontal and vertical rows of feet everywhere. I hadn’t seen anything like it before. They looked approachable, and climbed with a sense of ease. You had intermediates to grab, and multiple chips to shuffle your feet up to before you made your next move. It brought some of the exploratory part of climbing outdoors to indoors. Some of the most memorable climbs are ones that you can find your own way through, and BC was able to translate that to indoor routesetting.

Emphasis

Lines are not common in most types of climbing. The word “line” is often used to define the path up the wall you are taking, but it is rare that the holds will actually be in a line (don’t worry, I’m not forgetting about crack climbing). Lines of holds create emphasis on a particular section or wall or within a climb. T-nut placements on climbing wall panels are in a grid, which allows setters to have holds that are equally spaced apart.

Conversely, the holds could be screwed on in adjacent proximity which can place further emphasis on the line by reducing the visible wall space between the holds. A line is also a recognizable object. Climbing holds are often oddly shaped, non-symmetrical, and overwhelming to look at. Organizing these objects in a way that is recognizable to anyone regardless of their experience in the sport can help distinguish boulders from each other on a wall.

Pattern/Repetition

Our lives are built around patterns. We have a schedule for our day, we repeat tasks, and we generally can predict what comes next. Humans are creatures of habit. A pattern gives us the blueprint, and repetition builds our expertise. A line of holds is a tool to create a pattern in routesetting. They indicate the direction the climber is moving, which hands/feet they will be utilizing, and what type of hold they are using. The climber can formulate a plan to work through the pattern and execute it.

Repetition adds another layer of complexity. In routesetting, repetition can be considered lazy because it lacks variety. Is it more interesting to grab 3 different types of holds in a row or 3 of the same types of holds in a row? I don’t think there is a definitive answer, but there is something to be said in providing practice and clarity. In my opinion, commitment to a specific pattern and repetition of theme stands to give a more recognizable and memorable visual/functional experience. If two climbs have compelling movement, it's more likely that the “dynamic power pinch climb” would be memorable than the “dynamic power 1 pinch, 2 crimps, 3 slopers, 1 pocket” climb. Being concise, having a motif, and skill application offer a gratifying experience.

Movement

While movement is a design principle, movement is the routesetting principle. If a climb doesn’t move well, it’s going to be called awkward, which no-one or no-thing wants to be. Lines dictate how the climber moves through the space, and in my opinion, 3 holds in said line is the best way to create hand-over-hand movement.

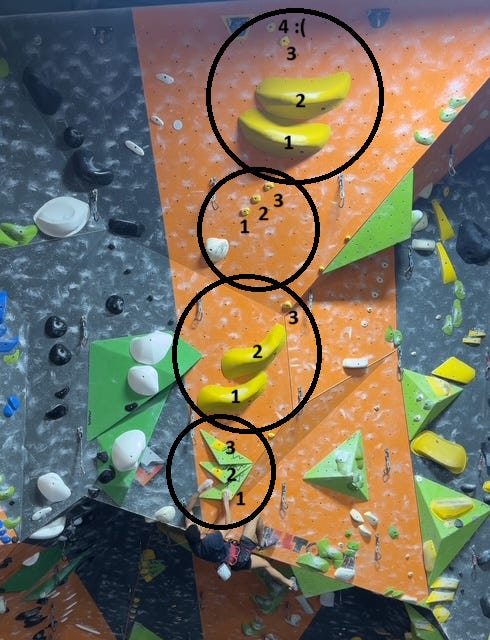

One of the first things I teach new routesetters is to think of their climbs in sections. A climb that is completely evenly spaced gives little indication to how the climber should be moving up the wall. Breaking it down into smaller bite-sized portions makes it easier to compartmentalize as a routesetter, and for the climber interacting with it. We can use the following route as an example:

There are four different sections on the route pictured, all made up of 3 holds (sorry, the last one is 4… I’m not perfect). There are small sections of overlap as shown by the bubbles, but there is not enough overlap to skip to the next section without increasing difficulty. There are multiple hand sequences that can be used, like bumping or crossing, but the climber will have to interact with all 3 holds before moving to the next section. This helps the climber distill the physical movement they will utilize.

Visually the climber is able to distinguish what holds they will be encountering as they move throughout the sections. I wanted to alternate using pinches and crimps for the route’s entirety, and each section reflects this dichotomy. While there is a larger line, the route can be sequenced section by section, with focal points directing the gaze to points of interest.

Odds or Evens?

Is one actually better than the other? No. Do I happen to use odd numbers more than even? Yes. This line of thinking came from the side of function before the side of aesthetics. I had been using this “odd hold” method as one of my easy-hacks-to-create-movement for years before I thought of it with more depth.

Maybe it comes from a deep even number aversion. When I order holds I get 3 of each macro, I recently got a 3rd ring for my right hand because I didn’t like having 2, and I get 3 McChickens when I go to McDonalds. Who knows!

Sound off in the chat, let me know if you’re Team Odd or Team Even and what your perfect grouping of holds looks like.

Well written. Who the fuck is Connor Perzely?

maybe I'll finally be able to send your boulders if I play Set every day

https://playset.netlify.app/